Victor Fet: «The world of soviet and russian culture has long been dead»

What does a long-time emigre, an American biology professor and a poet who writes in Russian think about the future of Russian culture? How does the experience of a natural scientist transform into the creative energy of poetry? What awaits the Russian language? Victor Fet, a zoologist, author of poems, translator and editor of poetry anthologies, answered questions from Radio Liberty.

– You write poetry in Russian, translate from English into Russian, and compile collections of Russian-language poetry. Having lived in the United States for more than a third of a century, what culture do you consider yourself a person of?

– Thank you for the difficult question. I grew up in the second half of the last century on what was created by a very thin layer of educated classes from the 19th century. After emigrating in 1988, I traveled to Russia four times, the last time in 2013. During a visit to Novоsibirsk in 2009, I was invited to speak on live television about education in the United States. «You are originally from Russia, you have lived in America for many years. Who are you loyal to: Russia or the United States?» the young host suddenly asked. And I blurted out: «Yes, I have lived in America for a long time, as a US citizen, naturally, I am loyal to America. I hope I will not have to prove this loyalty with weapons in my hands against Russia.» There were no more questions.

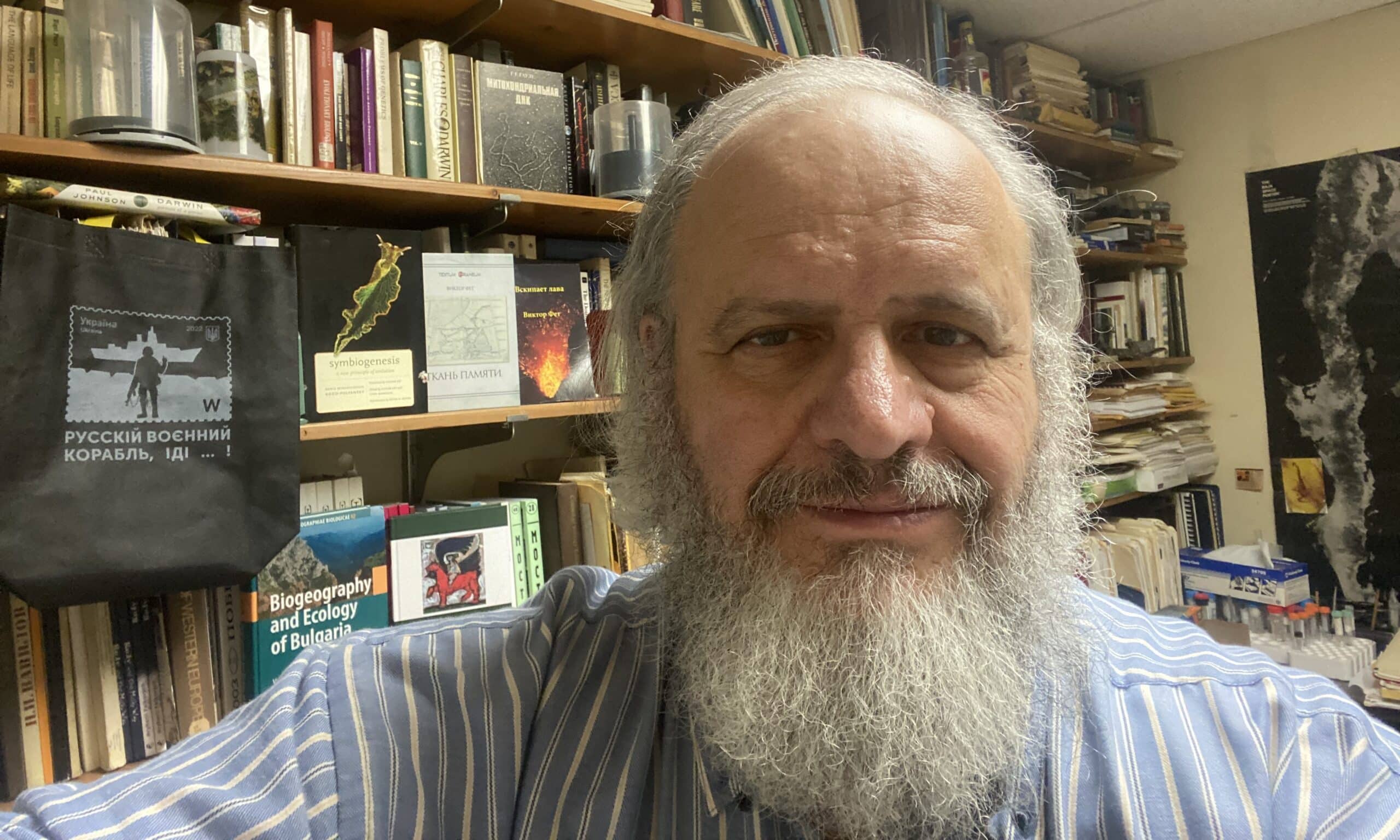

Victor Fet was born in 1955 in Krivoy Rog. He grew up in Novosibirsk. He studied biology at the Novosibirsk University (1971-1976), and was involved in poetry theater. In the summer of 1976, he left Siberia, choosing zoology and the deserts of Central Asia. He moved to the United States with his family in 1988. Since 1995, he has been a Professor of Biology at Marshall University. Author of works on the taxonomy and evolution of scorpions, editor and co-author of monographs on the biogeography and ecology of Turkmenistan and Bulgaria. He was the first to translate Lewis Carroll’s poem The Hunting of the Snark into Russian, organized the translations of Alice in Wonderland into several new languages, including Turkic ones. Author of 15 books of poetry and prose. Editor of the anthologies «The Year of Poetry,» which were published in Kyiv in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

– Putin has been in power in Russia since 2000. Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, has been fighting Ukraine since 2014, and has been doing so especially brutally for the fourth year now, with those who disagree with it being thrown into prison. What do you think about this?

– Undoubtedly, the people who are fighting against the ruscist regime today are heroes, just like the Decembrists and Herzen, like the eight dissidents in 1968 who went out to the Red Square «for your and our freedom» against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In today’s Russia, there is schizofascism, as has already been said. In my deep conviction, the imperial archaic project collapsed long ago, having suffered powerful shocks in 1917 and 1991, and is now breaking down under Putin and his henchmen. We are witnessing the collapse of an archaic, infantile matrix; at best, fragments-protectorates, Vladimir Sorokin’s «principalities-Rashastans» will survive.

– And the beautiful Russian culture?

– Here I have a radical, evolutionary view: I suspect that the world of Russian, Soviet, Russian culture has long been dead, they have all gone down in history somewhere at the level of Babylon. Only instead of cuneiform tablets we have digital clouds. I do not see a «beautiful Russia of the future.» It is difficult for me to imagine a future in which for Russian-speaking people anywhere in the world, Chekhov’s stories, Mandelstam’s poems, Ryazanov’s films or Vysotsky and Galich’s songs would have real value and could serve as the basis for a living culture. I think it’s appropriate to talk here not just about «culture» and other aesthetics, but about individual responsibility and ethics. Even if this sounds like outdated utopianism in the spirit of the Strugatsky brothers. But everyone develops their own language, digs out their own niche, and bears responsibility in conditions when human identity is capable of changing.

– Perhaps Russian literature will be saved by translations?

– Literary achievements often overcome the gravity of the original linguistic form, and even hereditary geography. A good example is the work of Vladimir Nabokov. In April 1917, he turned eighteen, and two months before that, the empire in which the future writer was born ceased to exist. Soon, the Nabokov family left Russia forever. Nabokov wrote his famous Lolita in English while traveling around the United States; the book was published in 1955 in Paris. The Russian translation made by the author himself was published in 1967 in New York. And now in the history of culture there is a Russian Lolita, an English one and numerous translations.

– Since we have mentioned Nabokov, he was seriously interested in zoology, and studied insects. What is known about the legacy of Nabokov the naturalist?

– We are not only colleagues, but also contemporaries: I learned of Nabokov’s death in the summer of 1977 from a Voice of America broadcast in Kushka, while working as a zoologist in the national parks of Turkmenistan. For many years I studied living beings: taxonomy, evolution, geography, animal conservation; I worked in the field from Mexico to Bulgaria, and especially in museums in many European countries. The museum subculture, like the expeditionary one, is very specific. Many know this from painting or archeology; the same applies to specialists who work with collections in natural history museums.

And Nabokov knew this very well, too. Upon his arrival in America, he worked for some time at the Harvard Zoological Museum, where he was even paid a little. Later, he was offered a position as a teacher of Russian literature at the small Wellesley College. Who knows, if fate had turned out differently, he could have taken a professional niche as a zoologist in some museum in America or Europe, drowning, as he wrote in his youth, «in the bright circle of the microscope.»

Many years later, I dared to depict him in a fantastic poem-dialogue «Nabokov and Kholodkovsky.» Then I became interested in zoological motifs in Nabokov’s work. In 2003-2015, I published a number of articles and notes in the journal The Nabokovian, and a chapter about his childhood studies of entomology in the book Fine Lines: Vladimir Nabokov’s Scientific Art, published in 2016 by Yale University and entirely devoted to Nabokov’s zoology. It is now quite clear that Nabokov was a solid professional. In many of his novels he hid purely zoological riddles, some of which I was lucky enough to solve.

– So it turns out that butterflies and scorpions, forests and deserts are responsible for the person they tamed?

– Zoology and geography, I think, were extremely important in my case, as in Nabokov’s, for the creative energy that is transformed into literature. In Central Asia, where I worked for many years, the deserts are full of scorpions, and in the last 30 years I have collaborated with many colleagues from Europe. Little-known scorpions live there in the mountains and on the islands from Switzerland to Greece! Having survived from ancient times, they carry within themselves, as in a time capsule, all the genes of the past. Studying them, we are never at a loss. If we find something in common with others, therefore, it is of the most ancient origin. If we find something unique for scorpions, it means that it appeared only in this branch, perhaps in ancient times, and has survived to this day.

Humans have no sense of deep time. It is difficult to feel a thousand years, let alone the difference between two and twenty million. One has to rationalize, to reason. The accumulation of understanding of animals or processes also goes into the construction of new emotional landscapes. Dealing with scorpions, we easily operate with figures of about three hundred, four hundred million years – on such a scale, where the origin of not only the Cenozoic youth like snakes or whales, but also the venerable reptilian trunks of the Mesozoic is lost. My scorpions are truly «living fossils,» little changed since those unimaginably ancient times when there were no birds in the sky, no dolphins in the sea, no flowers in the meadows, and there could not possibly be meadows themselves. An ancient, terrible world, alien to humans and insignificant to us – but it can be understood and described by the power of imagination, based on knowledge.

– How long have you been writing poetry? And to what period does your Russian language belong?

– I have been writing poetry for undoubtedly longer than I have been writing scorpions. My father wrote down lines that I rhymed in the manner of Marshak, Chukovsky, Zakhoder, who were read to me then, when I was 4 years old. At school, I wrote parodies and imitation poems in the spirit of Pushkin and Mayakovsky. As a student at Novosibirsk University, I wrote song lyrics, scripts for skits and student theater. I even managed to publish a parody of Yevtushenko in the Krokodil. In my early poems, of course, I largely followed the light genre, where «physicists joke». Then I became serious. I believe that the division into physicists and lyricists, or «two cultures», is artificial: both hemispheres must be involved.

After university, I worked for more than ten years as a zoologist in Turkmenistan, practically in exile, where my Russian became quite individual. At 32, I moved to the United States with my family. My language is from the mid-1970s, and it has remained that way, like an insect in amber… Naturalists observe and study the changing picture of the world. And I tried to do this using traditional verse. Valery Bryusov spoke of «scientific poetry»; new landscapes were opened up in the 20th century by natural sciences from physics to genetics. After all, our instruments, rhymes and meters (and especially iambs!) are so seductive that their very existence, their accessibility seem like the greatest success, inspiring a game of words, sounds, rhythms.

– Three years ago, the orderly European life collapsed. And how does it look from America?

– And my world in the quiet American hinterland also collapsed. Pre-war literary and natural-philosophical discussions and studies, the few attempts to establish contacts with the Russian metropoly remained in the past. From the very first moment of the war, I had a feeling of shame that my country, the United States, did not rush to help, did not dare to confront the aggressor, did not close the sky from the bandits – just as in 2014 the world resigned itself to the occupation of Crimea and Donbas.

It was impossible to stay on the sidelines. I had to decide how I could most effectively help the fighting Ukraine from here – in addition, of course, to private donations, fundraising, lectures about Ukraine. I had previously been on the editorial board of a zoological journal in Kyiv, but of course that wasn’t enough now. So, I chose two types of volunteer work, which I’ve been doing for three years now.

I live on the Ohio River, at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains in West Virginia. Our Huntington is a college town, like the ones known from Nabokov’s novels Pnin and Pale Fire. On the university platform in Microsoft Teams, my colleagues and I organized a weekly volunteer video podcast MUkraine (MU is an abbreviation for Marshall University), and held 160 educational meetings in English over three years. We invite speakers from all over the world, such as an American Ukrainist Alexander Motyl, historian Yuri Felshtinsky, philosopher Mikhail Epstein, artist Ekaterina Margolis, writer Carina Cockrell-Ferre, Ukrainian children’s poet Grigory Falkovich, translator of Dante into Ukrainian Maksym Strikha, international group of translators «Kopilka,» poet Tatyana Voltskaya, philologist Oleg Lekmanov, and many others.

The main and special thing in all this is that we work in English. Our audience is the average American student or even a university professor, who usually knows very little about Eastern Europe and the first thing they ask is: «Wasn’t Ukraine part of Russia?»… What my colleagues and I are doing is a special kind of work, difficult and rather thankless, but I am sure it is extremely necessary, judging by what is happening now. In February 2022, we entered a zone of extreme turbulence – and I think for a long time.

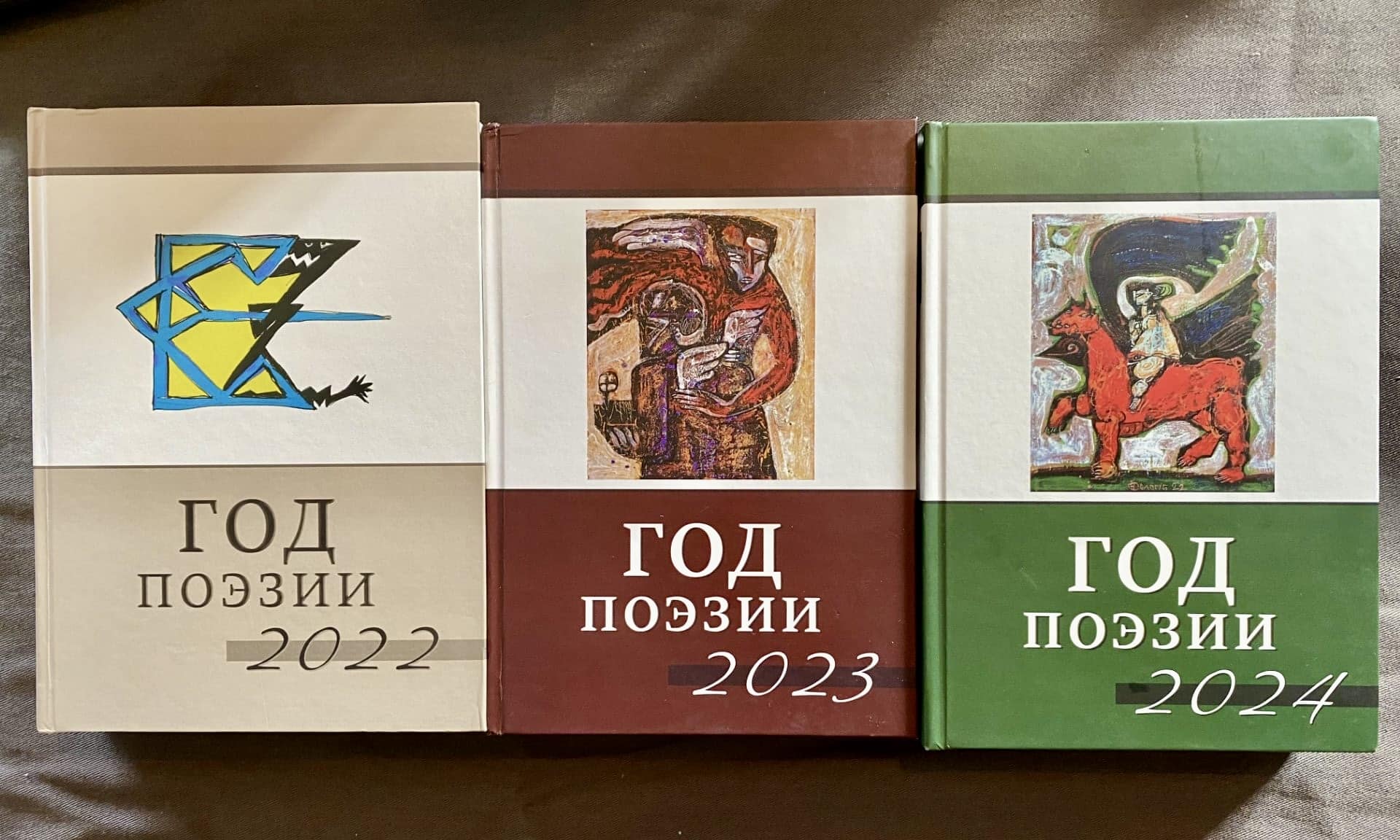

My second main occupation today is publishing and editing in Russian. From 2019 to 2022, I was the compiler and editor of four volumes of the anthologies Day of Russian Foreign Poetry, which were published in Frankfurt. After February 2022, we published three volumes of poetry anthologies Year of Poetry, in the wonderful Oleg Fedorov Publishing House in Kyiv, 500-600 pages each. These books are freely available in electronic form on the publisher’s website.

I am convinced that the publication of such Russian-language books is important for international support of Ukraine, which is defending itself from Russian aggression. Each volume of our anthology has up to a hundred authors, every third author is from Ukraine, others are from the USA, Israel, Europe. Already in the fall of 2022, I wrote: «We are the last ones who wrote before the war, / in a simple language that has not yet been killed, / and now it is difficult for us to communicate with it, / separating it from its country, / although it has long been alien to us, / like its feral people…»

– You recently predicted the «death of the Russian language». Are we really heading towards the fire?

– I always imagined writing poetry as a kind of craft that implies repetition, endless variations on a theme. This is how, say, a master works on a potter’s wheel, whose goal is not to create a unique work like a novel or a painting; the meaning of his work is precisely in constant repetition with variations, in the production of objects of applied art. And poetry seemed to me to be precisely this kind of game – not a game in the sense of a child’s or gambling game, but a game of Hermann Hesse’s glass beads or a musical instrument. Stravinsky also complained that Vivaldi wrote 200 “identical” concertos. And painters also create dozens of similar landscapes.

When Russia occupied Crimea in 2014 and came to Donbas with weapons, I stopped writing poetry; I thought I had written everything I could. And after February 24, 2022, I felt like a radio that someone turned on and forgot to turn off. I listen through the jammers of memory and reason, twist the vernier, peer and write down as quickly and in detail as possible, sometimes two or more poems a day, each one seems like the last. It turned out to be an uninterrupted poetic diary, which has grown into a corpus of over 800 poems, about 30,000 lines. About 40 poems, written in the spring of 2022, were included in my first wartime book, Lava Boils. After that, four more books of poetry were published, all in Kyiv. For three years in a row, these requiem poems (being a requiem of the language itself, as noted by the remarkable musicologist and essayist Vladimir Frumkin, who has long lived in the suburbs of Washington) have been materializing almost daily. Perhaps previous generations felt the same (just look at the diaries of Zinaida Gippius) – but! they did not live in a digital world, where the rules of the game have changed, from transparency of history itself to deepfakes of artificial intelligence.

– Almost 150 million people in the world call Russian their native language, where will they go?

– It’s not even a question of how many native Russian speakers will formally remain in the world – the point is that the history of the society that used this language is ending very quickly (the trail of cultural heritage of the past, from its Golden Age to the Silver Age, has long been cut off). A hundred years have passed since Wrangel’s army evacuation from the Crimea to the Upper Lars on the Georgian border. A million people who fled since 2022 are «voting with their feet» against their Russian stepmotherland. The Russian language will not suffer the fate of Latin (which gave birth to new languages), nor English or Spanish (survivors of collapsed empires), and certainly not Hebrew (revived by surviving enthusiasts).

History is accelerating. My experience as a zoologist and writer tells me that only the group that managed to acquire exceptionally important adaptations, as we call them in evolutionary theory, will survive. After all, the dinosaurs did not die out completely: one of their branches turned into birds. However, they paid for this with specialization, becoming flying machines that lay eggs.

We, mammals, have a completely different modus: we (females) bear children inside our bodies, having acquired a completely special relationship with the offspring. Hence the selection for a special immune system, behavior, communication, language and, apparently, intelligence (in birds, which are not related to us, it is different, even in the smartest crows).

I recently had the opportunity to teach an honors course for our best students, «Biology and Science Fiction,» covering H. G. Wells, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Karel Capek. In 1895, Wells’s dystopia The Time Machine was published in Great Britain. In it, he looked 800,000 years into the future with its Morlocks and Eloi, the descendants of the Victorian man. And it seems that today’s humanity willingly splits not into two, but into hundreds of species, each on its own, with its own culture and degree of responsibility, with its own information bubble.

I hope that someone hears me at least in our bubble, on our Mobius surface.

The translation was made by Victor Fet

- Война касается каждого. Солидарность с Украиной - 2 марта 2026

- Війна стосується кожного. Солідарність з Україною - 2 марта 2026

- Прибежище свободы в рае Ксении Букши - 26 февраля 2026

Images:

Victor Fet (© Personal archive)

Nabokovs. Butterfly Hunt. (Courtesy Photo)

Three volumes of the anthology Year of Poetry (Kyiv) (© Personal archive)

The MUkraine podcast group: Larry Sheret, Kateryna Rudnytska Schray, Anara Tabyshalieva, Victor Fet (© Personal archive)

Поделитесь публикацией с друзьями